1924 Europe Trip Photos

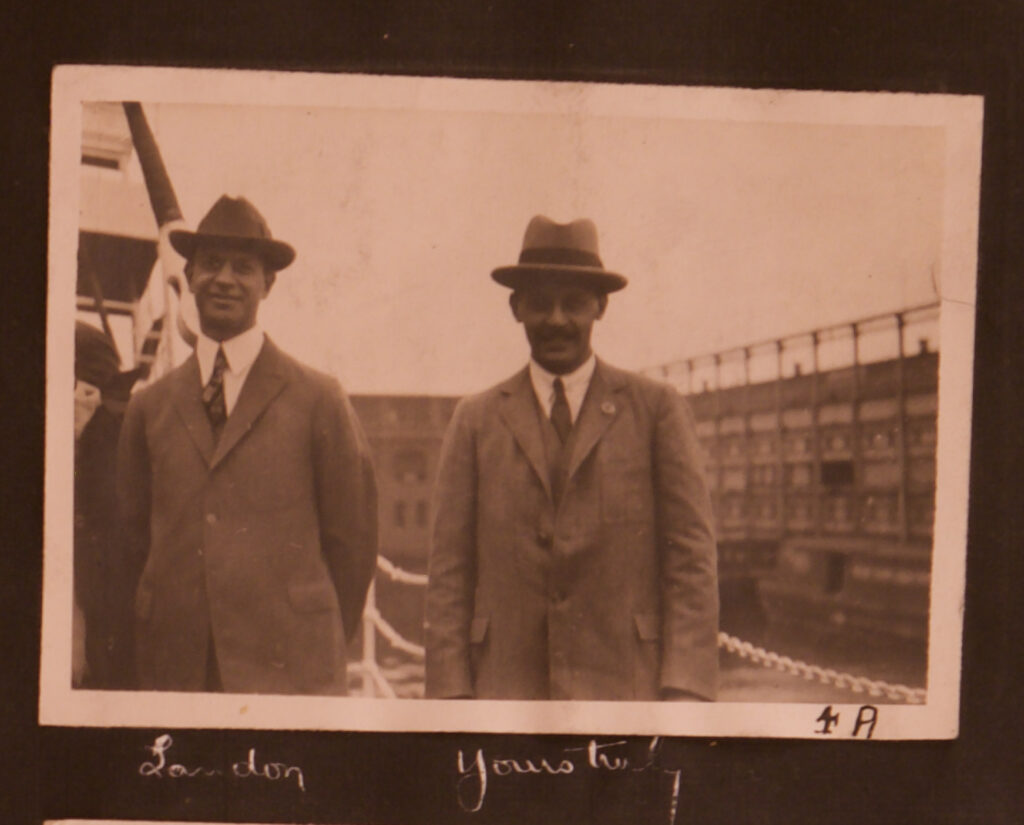

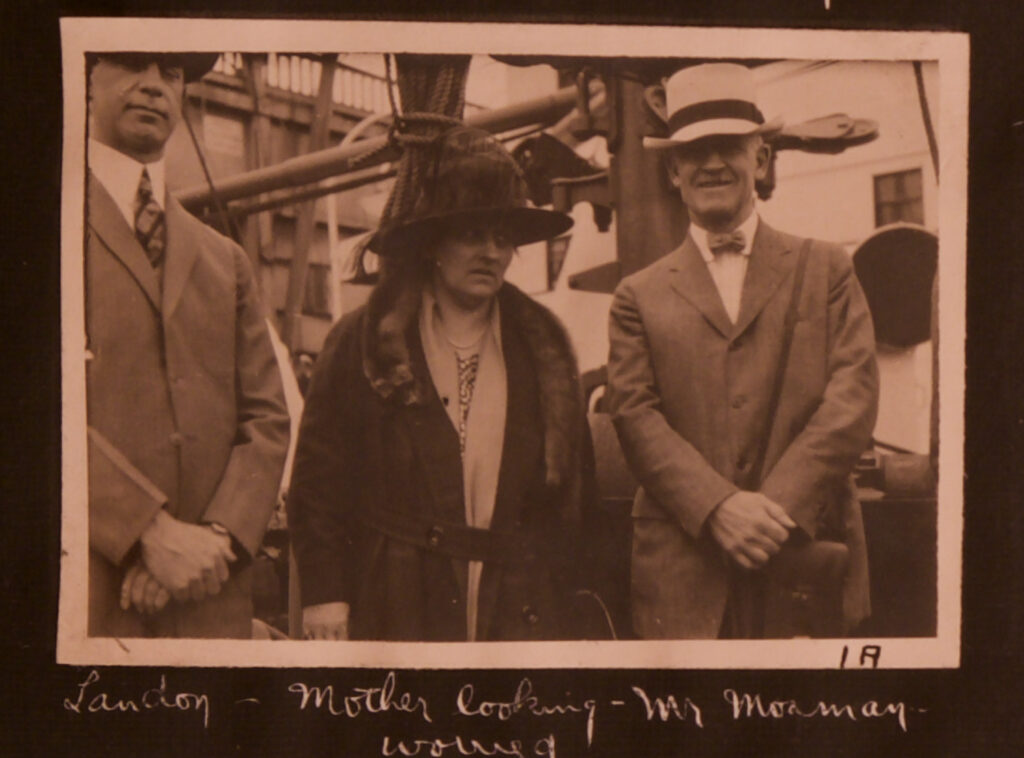

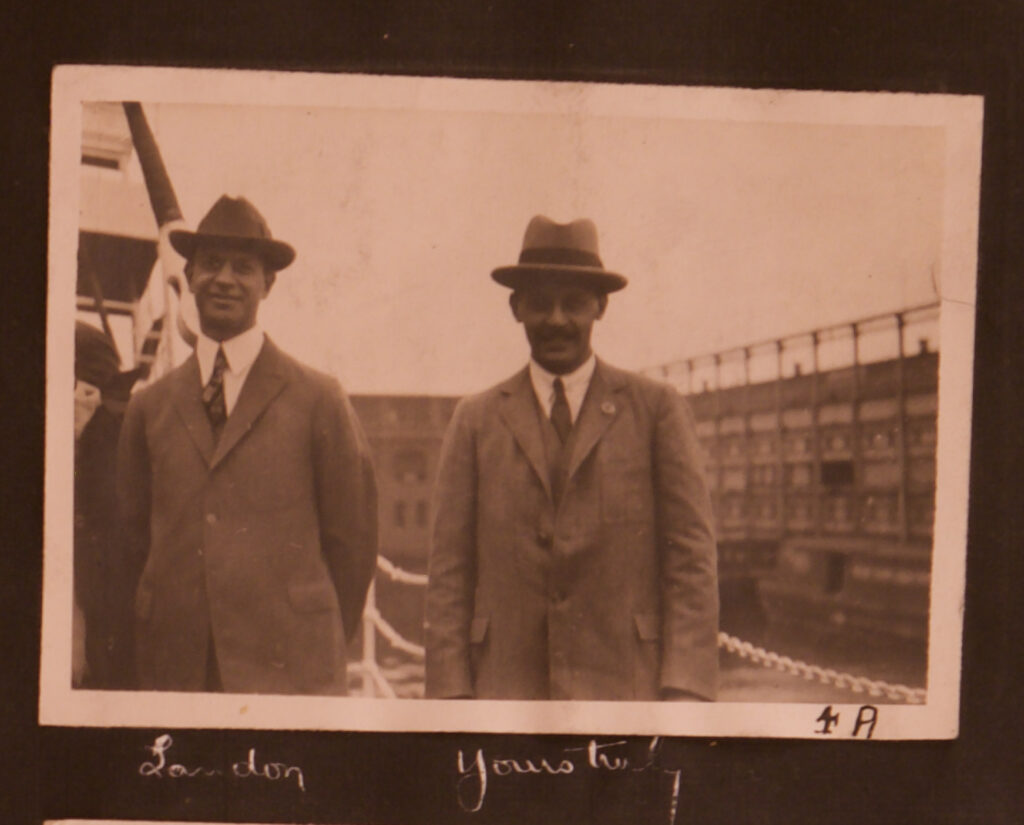

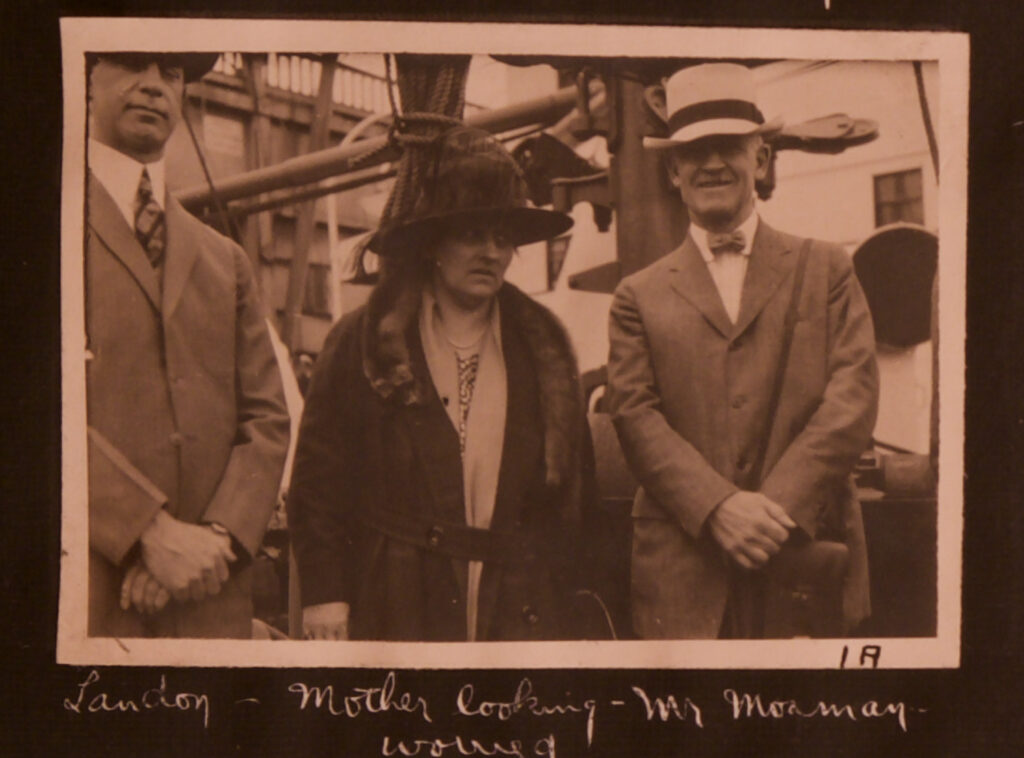

Here are some photos that include Landon Strobel from the 1924 Eilers family trip to Europe. Brothers Fritz and Farny Eilers traveled around Europe and North Africa by car.

Here are some photos that include Landon Strobel from the 1924 Eilers family trip to Europe. Brothers Fritz and Farny Eilers traveled around Europe and North Africa by car.

Suzanne, it turns out I didn’t mark many photos with the Strobel name, so it will take me time to assemble some Strobel related photos. Here are a few that might interest you:

This 1893 photo was from George Ratcliff, who has since passed. It is really faded:

This 1903 photo shows the Strobel family in Salt Lake. It was in an Eilers family album. Another not so great photo, but I do have other photos of Eilers/Strobels in the Salt Lake area, but just have to locate them:

In 1924 the Eilers and a few others, including Landon Strobel, left for Europe. My grandfather, Karl Eilers, and his brother Farny spent time deriving around Europe. I believe Landon accompanied them part of the way? Anyway, Landon is shown, at the very least, in the top photos. My cousin Anita Eilers Graves has this album:

You may have these .. photos at the Wurlitzer property in Cincinnati with names (from the George Ratcliff family) (I have higher resolution of these photos):

Here’s a photo of my copy of the large family tree that was created circa 1932:

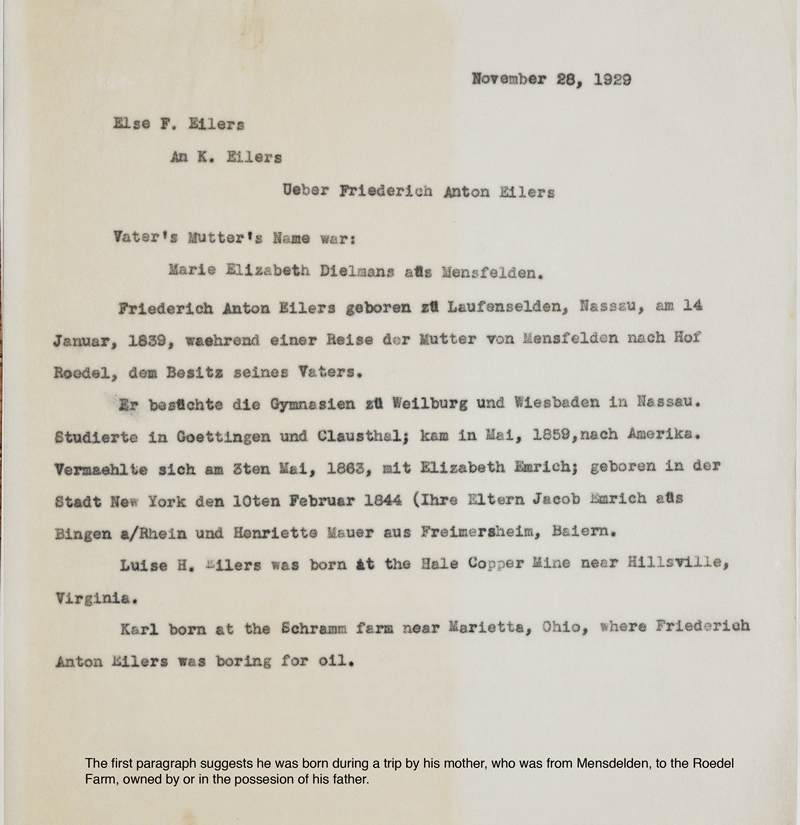

This note was dated November 28, 1929, and discussed Anton’s birth.

November 28, 1929

Else F Eilers And K. Eilers

Ueber Friedrich Anton Eilers

Friederich Anton Eilers geboren zu Laufenselden, Nassau, am 14 Januar, 1839, waehrend einer reise der mutter von Mensfelden nach Hof Roedel, dem Besitz seines Vaters.

Er besuchte die gymnasien zu weilburg und wiesbaden in Nassau. Studierte in Goettingen und clausthal; kam in Mai, 1859, nach Amerika. Vermaehlte sich am 3ten Mai, 1863, mit Elizabeth Emrich; geboren in der stadt New york den 10ten Februar 1844 (Ihre Eltern Jacob Emrich aus Bingen a/Rhein und Henreitte Mauer aus Freimersheim, Baiern).

(switches to English)

Luise H. Eilers was born at the Hale Copper Mine near Hillsville, Virginia.

Karl born a the Schramm Farm near Marietta, Ohio, where Friederich Anton Eilers was boring for oil

Rough Translation:

Anton born to Laufenselden, Nassau, on January 14, 1839, during a trip to the mother of Mensfelden to Hof Roedel, the possession of his father.

He attended high schools In Wiesbaden and Weilburg in Nassau. Studied in Goettingen and Clausthal; came in May 1859, to America. Married on the 3rd May, 1863, to Elizabeth Emrich, who was born in the city of New York, February 10th, 1844 (Her parents Jacob Emrich of Bingen a / Rhein and Henreitte Mauer of Freimersheim, Bavaria).

Original Letter:

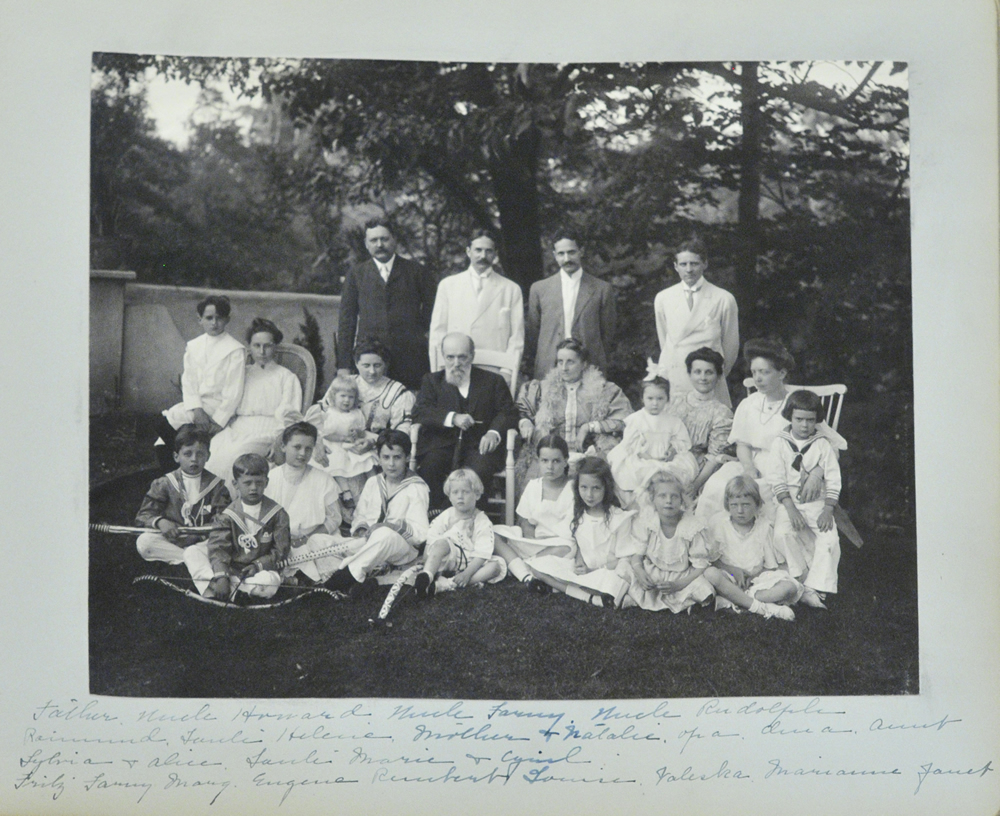

This family photo of the Wurlitzer family was taken in Cincinnati, Ohio. Family members in the legend below the photo are described from the point of view of the Eilers children (Marguerite, Fritz, and Farny). Hence, “Father” is Karl Eilers, top left.

Back Row: Karl Eilers, Howard Wurlitzer, Farny Wurlitzer, Rudolph Wurlitzer, Jr.;

Next Row: Raimund Billing Wurlitzer, Helene (Billing) Wurlitzer, Leonie (Wurlitzer) Eilers (on lap Natalie “Patsy” Wurlitzer), Rudolph Wurlitzer, Leonie (Farny) Wurlitzer, Sylvia (Wurlitzer) (Wienberg) Farny (Alice Farny on lap), Marie Wurlitzer (Cyril Farny on lap);

Front Row: Fritz Eilers, Farny Eilers, Marguerite Eilers, Eugene Wurlitzer, Rembert Rudolph Wurlitzer, Louise Henriette Wurlitzer, Valeska Helene Wurlitzer, Marianne Leonie Wurlitzer, Janet Wurlitzer.

Other photos from the same period:

(See expanded list of charges two weeks subsequent to the charges presented below)

THE TEN CHARGES ON THE RESOLUTION SUBMITTED AT AMERICAN SMELTING & REFINING’S SHAREHOLDER MEETING IN APRIL OF 1921:

10. The use of the company’s funds and facilities and the time of its highly paid officers and of its employees for investigations of properties for the benefit of the Guggenheims, for the solicitation of proxies and efforts to perpetuate the control of the Guggenheims and to extend their strangle/hold on the company and its property.

Below is the letter from Karl Eilers to Maxwell Hahn about an upcoming biography by Hahn on Eilers for a German newspaper. The German version can be found here.

March 15 1938 Letter from Karl to Mr. Hahn

Mr. Maxwell Hahn

Room 1811–570 Lexington Avenue .

New York City

My dear Mr. Hahn:

I was much pleased with your biographical article concerning myself, and I have done as you suggested– made a few corrections in pencil; also, I am having your article re-written, with some copies for my children.

On your last page you make a very nice and very proper comment about Frank Van Dyk. I wish you could also say something to the effect that I am very grateful for the friendly, congenial assistance given me and our Associated Hospital Service by Homer Wickenden and yourself; and if you do not think it would clutter up the article too much, I would also like to have recognized the fine assistance given us by Mr. Pyle, Wm. Breed, Jr., Mr. Stanley Resor, and the many other important members of our Executive Committee and the Board. I had thought that something could be said immediately after your paragraph about Frank Yan Dyk covering Homer and yourself. Perhaps to add the other names at this point might be too cumbersome; but if your ingenuity could work it in somewhere advantageously, I should like very much to have it.

Very truly yours,

enc.

KE/S;

=================

Maxwell Hahn’s biography draft of Karl Eilers (English Version):

“Because I wasn’t worried, and because I had confidence . . .”

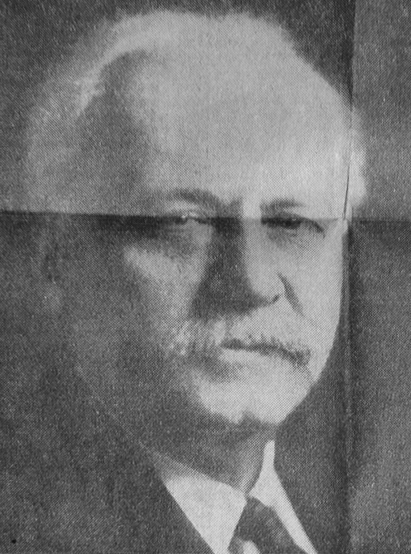

With these words, Karl Eilers, American-horn son of a German father, explains how he has traveled the long road from his birth seventy-two years ago in a small Ohio town to a position of prominence in New York City as President of the Associated Hospital Service of New York and President of Lenox Hill Hospital.

Today tall and portly, with the erect carriage of an army officer Karl Eilers is as full of confidence and faith in the future as in his youth. White-haired now, he goes about his tasks with the energy of a younger man and greets each day with the zest carried over from his colorful and adventurous past.

He has watched the Associated Hospital Service grow until now more than 650,000 men, women and children in the New York metropolitan area are enrolled and entitled to hospital care when needed. The skeptics who questioned the non-profit three-cents-a day plan for hospital care at its beginning less than three years ago have found their answer in the fact that subscribers have share and individually saved more than $3,7l5,000 in hospital bills.

And with the faith that enabled him to accept the presidency of the three-cents-a-day plan when others were doubtful of its success, Karl Eilers is convinced that enrollment in the plan will exceed in in York City a million members by the end of this year.

Mr. Eilers’ confidence in the idea of placing hospital care on the family budget for payments of a few cents each day has been strengthened by the confidence of the public.

But for a decision made eighty years ago, Karl Eilers might have been a ministers son, pursuing his destiny in Clausthal, in the Harz Mountains, Germany.

The decision was wade by his father, F. Anton Eilers, who, given the choice of the ministry or mining for a life’s work, decided to be a miner. He was sixteen at the time, and from America came reports of a great Western territory as yet hardly touched, and of minerals that slept under the grass roots, ready to yield their wealth to the finder.

And so, in 1859, Karl Eilers’ father came to America. He brought his small savings and a stout heart to a country soon to be torn with internal conflict. Slavery, not minerals, was the subject he heard discussed at every corner. In that year, a man named John Brown had led a raid on Harpers’ Ferry in Virginia to incite a slave revolt. John Brown was killed, but the issue grew sharper and sharper. There were rumors of war in the air. Disturbing rumors to the ear of the young man who had left a quiet home in Germany.

He found a Job in a clothing store on Chatham and Pearl Streets, and a place to live in the Tremont section of the city. He worked there for several years, meanwhile seeking an opportunity to carry out his determination to be a miner. In 1861 Civil War was declared. Mr. Eilers remained in New York. In 1863, when he was courting the girl who was to be Karl Eilers’ mother, the draft riots broke out in New York City and left 1,000 dead to decide whether or not Republican officials had stuffed the draft lists with the names of Democrats. But the violence of the times proved no handicap to romance and in that year Mr. Anton Eilers married.

Shortly after his marriage, he left the clothing store where he had been employed and started his career in the mining industry in an assay office on Park Row. His employer was Dr. Rossiter W. Raymond of Adelberg & Raymond, assayers.

Mr. Eilers and his young bride traveled about the country from one mining operation to another. In 1865, while with a company drilling for oil near Marietta, Ohio, his son, Karl Eilers, was born.

The first American-born son of the Eilers family opened his eyes in a perplexed country. Abraham Lincoln had been shot and torn from the helm of the nation when it most needed guidance. Andrew Johnson was inaugurated president of the United States and assumed leadership of a broken and uncertain people.

The family returned to New York and took up residence in the Morrisania section of the city. Young Karl Eilers developed into a tall husky boy, receiving his first formal education at a public school in the Melrose section. His father was advanced to the position of Deputy Mineral Surveyor. Dr. Raymond had become United States Com-

miasionor of Mining Statistics for the western part of the United States and had six men scouting around the country, gathering information concerning the mineral resources of the nation.

In 1873 Karl Eilers witnessed his first financial panic and saw a city demoralized. With business structures tottering the depression began with a series of bank failures on September 20. The Stock Exchange closed that day and remained closed until September 30. Dr. Raymond retired from his position in 1876. Karl Eilers’ father also resigned, and went to Colorado to investigate the copper resources there at the request of a Boston organization.

At Saints John, Colorado, Karl Eilers received the first indication that his life was one curiously favored by fate. He was in the flimsy shelter of a small smelting plant that had been set up at the foot of a towering mountain. He stood watching the progress of a rainstorm that had been raging about him for hours when he heard a roar as though the whole mountain were collapsing. Tree-roots, loosened by the torrents of rain, gave way. Tons of earth crumpled and roared down the mountainside, throwing a barrage or trees and rocks into space. It was useless to run. Karl Eilers watched the mountain as it flattened and spread towards him. When the slide had spent itself, the twisted trees and broken rocks were piled a scant fifty feet from the plant there Karl Eilers stood and breathed thankfulness.

Mr. Eilers left the exciting life he had led with his father in the west and returned to New York to study at the Hill School, Pottstown, Pa., and at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute in 1883. Later he took courses in mining and metallurgy at Columbia University.

In 1889 he finished his studies in America and returned to his father’s native Germany to study in Berlin. Interested in European mining operations, he visited France May, 1891 to see the mines there. While in Paris, he studied Spanish in preparation for a trip to Spain. He left for that country in fall and lived for several weeks at the American Embassy. Later he traveled through the southern part of that country, inspecting mining conditions.

Karl Eilers returned to the United States in 1892 and, like his father, arrived at a time when the country was in upheaval. Labor trouble had swept the land. Riots were frequent. He joined his father who had become a power in the mining industry and worked with him. In 1894, that industry, too, became the target of labor manipulations. A nation-side strike of miners paralyzed operations throughout the country. Again, the Eilers weathered the storm, moving alertly from one organization to another.

In 1896 at the age of thirty, Karl Eilers married. He had acquired a reputation by that time for his knowledge of smelting theory and practice, and in 1900 was sent to organize a lead smelting plant that the American Smelting and Refining company had built in Utah. The Guggenheins had taken control of the American Smelting and Refining Company in 1901, and his association with them lasted until 1920 when he parted company with Simon Guggenheim and his organization.

Recalling the problems met during his smelting career, Karl Eilers remembers that their troubles were not all under ground. The smoke that poured in great volume from the chimneys of the smelting plants made the smelters unpopular with the eastern farmers, and lawsuits were frequent. The farmers protested that their crops and animals were stifled by the rolling clouds and carried their complaints to the courts. Efforts were made to change this condition by building the plants at the mouths of canyons and valleys so that the smoke would be swept out and up by the air currents. These efforts were futile, however, and the smoke continued to sweep over the land for a radius of twenty-five miles and more from whore the plants were constructed.

But that, and the mountain slides, forest fires and ruggedness was part of the expansion and development of the West in which Karl Eilers played such an active part, It was to be, if cities were to grow where forests and empty plains stretched limitless and forbidding.

The men who met and solved the difficulties of that forced and hurried growth of a nation had to have confidence, they had to be unafraid.

In New York four years before Karl Eilers was born the second and more peaceful half of his destiny began shaping itself. The German Hospital and Dispensary was founded in 1861. Because of Civil War, the first building was not completed until 1868 although six beds were then in use at the dispensary which had been establish at 8 East Third Street.

It, too, expanded and developed. Now known as Lenox Hill Hospital, with modern buildings at 111 East Seventy-sixth Street it has taken its place as one of the leading hospitals in New York City.

When Karl Eilers was invited several years ago to become a member of the board of trustees of the hospital, he accepted because he ‘considered it a civic duty.’

Today, as president of Lenox Hill Hospital, he continues to regard his position as a fulfillment of a civic duty, one more contribution to a community he loves.

In 1934, he was asked to accept the presidency of the Associated Hospital Service of New York, a non-profit community organization that planned to put hospital care on the family budget of the man and woman in the metropolitan area for payments of a few cents a day.

There were critics of the idea, and others who warned Karl Eilers that it would not work.

“Why become associated with an organization that is pre-destined for failure”, they argued.

Enrollment rates had been estimated at $10 a year for a single subscriber. They were too low, the doubters pointed cut. Too many hospital benefits were provided, the cost of operation would be too great. And, anyway, the public would not be interested.

Karl Eilers shrugged his heavy shoulders. It was not a new idea to him. For in Pueblo, Colorado, many years ago, the miners and smelters had agreed upon a similar plan to ensure themselves proper care in times of illness and injury. From each man’s monthly rage was deducted a certain sum which was put into a central fund. From this fund, the money was taken when needed for medical care. The plan had worked well and served its purpose. And Karl Eilers had confidence in this plan to serve millions of people in the New York metropolitan area. He accepted the presidency.

Today, more and more people are learning that they don’t have to worry about unexpected hospital bills. Letters pour into the headquarters of the three-cents-a-day plan at 570 Lexington Avenue from grateful subscribers, stating that, because of their membership, they have been able to meet the problem of unexpected hospitalization without financial concern. The bills are paid in advance.

Every day, 1,198 incoming calls are handled by Associated Hospital Service telephone operators. Most of the calls are from persons who want to know more about the plan and its methods of enrollment. The doubters have been silenced, and Karl Eilers maintains his well-placed confidence in the plan and the people who are responsible for its success.

The three cents-a-day plan has upheld its standards as a non-profit community service. If it were otherwise, it is doubtful whether Karl Eilers would be associated with it.

He speaks proudly of Frank Van Dyk, executive director of the Associated Hospital Service of New York, and credits him with the growth of the plan and the extension of hospital benefits to subscribers.

[Large empty gap in the draft document at this location between the paragraph above and below. No obvious reason why]

He is proud, too, that as president he never interferes with the activities of his executives.

“One of the biggest things I have learned is to keep my hands off the man who is doing the work”, Karl Eilers explains. “I believe it was the father of John D. Rockefeller, who said, ‘Find the man that knows more about your problems than anyone else, put him in charge, and then let him work them out’”.

He looks up from his desk and smiles. Not a young man now, but certainly not an old man. With a past already filled with rich memories, he keeps his eyes to the future and the opportunities that may be in it for him to serve the community further.

Karl Eilers might have been a minister’s son, resigned to old age in Clausthal, in the Harz Mountains, Germany. He might have failed in the West and been swept aside by the waves of progress. He wasn’t.

“Because I wasn’t worried, and because I had confidence—“.

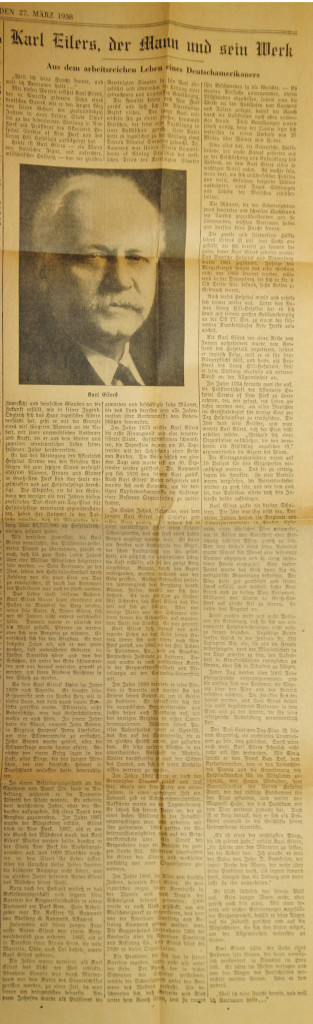

This article about Karl titled “Der Mann und Sein Werk” appeared in a German newspaper March 27, 1928. It was written by Maxwell Hahn. The english translation can be viewed here.

Arthur S. Dwight was a friend of Karl’s since they were boys. He was also Rossiter Raymond’s nephew. Arthur was a mining engineer who worked for Anton Eilers and with Karl Eilers for several years.

Karl Emrich Eilers, Engineer of Mines, Master of Science (Hon.) Honorary Member, Director and Treasurer of the Institute, one of the most distinguished and probably the most widely beloved of its members, died at his Sea Cliff, Long Island home on August 18, 1941. In spite of failing health, he had continued his activities to the end. He was seventy-five years old.

He was born at Marietta, Ohio, on November 20, 1865, the son of F. Anton Eilers and Elizabeth Enrich Eilers. While his family was later residing in the far west he attended the Hill School, Pottstown, Pa., was roommate of my cousin, Alfred Raymond and spent his vacations in Brooklyn with his roommate’s family, where I came to know him intimately. Later he graduated from the Brooklyn Polytechnic, and in 1889 from the Columbia School of Mines, following which he went abroad to take some courses in the German mining schools and to visit foreign metallurgical plants.

In 1896, after his establishment in active work in Colorado, he married Miss Leonie Wurlitzer of Cincinnati, Ohio, and had three children, Marguerite (Mrs. Andrew Beer) K. Fritz, and Farny, all of whom, with his widow survive him.

For me to describe his career is like telling my own story, up to a certain point, for he was my boyhood friend, my close associate in metallurgical work in the west, during which our professional careers were moulded by the same influences, and after our professional paths diverged, though still closely parallel, he remained an unwavering and loyal friend.

The background of the story is the lifelong friendship of Karl’s father, the late Anton Eilers, with my uncle, the late Dr. Rossiter W. Raymond, one of the founders of the Institute and its Secretary for over 30 years. It also involves some of the ancient history of the development of lead smelting in the west. The elder Eilers, after graduating from Clausthal Mining School, came to this country in 1859. In 1863 he became one of a group of young mining engineers on the staff of the firm of Adelberg & Raymond.

Having proved his abilities, Eilers was selected by Raymond in 1869 as his Deputy Commissioner of Mining Statistics, in helping gather and edit the voluminous data on mineral resources of the West, which they verified by personal visits to the western mining camps. The record of their work is to be found in the 8 volumes of “Raymond’s Reports” covering the period of 8 years ending in 1876. This long’ and intimate association of the two men resulted in a close intimacy of their families, influencing profoundly the careers of Karl Eilers and myself, and indirectly those of many others.

Anton Eilers, by the wide knowledge of the mineral resources of the west gained by his extensive travels, saw the great opportunities offered by the lead-silver deposits of the Utah and Colorado districts. In 1876 he acquired an interest in the Germania Smelter at Salt Lake. In 1879 soon after the opening up of the extensive carbonate deposits at Leadville, Colo., he formed a partnership with the late Gustav Billing and built a lead smelter in Leadville. Under the improved smelting technique which Eilers developed this plant had a very profitable career at the height of the Leadville boom and, after its sale the Consolidated Kansas City Smelting as Refining company, became known as the Arkansas Valley Smelter. It is today, under the ownership of the American Smelting & Refining; Company, the only lead smelter of all the dozen or more of its one time competitors still operating in Colorado. The old log cabin which Eilers built as his office is still standing.

On the dissolution of their partnership Mr. Billing purchased the Kelly mine and built the Socorro Smelter in New Mexico, afterwards acquired by the St. Louis S. & R. Co. Anton Eilers formed a company with the owners of the Madonna mine at Monarch, Colorado under the name of the Colorado Smelting Co. and in 1883 built his smelting plant at Pueblo, Colo. The Madonna ore, a carbonate lead ore, low in silica and high in iron oxide with an average tonnage of over 150 tons per day for several years, formed an ideal smelting base, and with cheap fuel and limestone enabled Eilers to compete for the profitable silicious ores at his own figures. The plant though not as large as some of the other smelting works in Colorado was excellent in design, and with the many structural improvements introduced by Eilers and his standardized slag formulae, his works became famous as a model in design, or orderliness and efficient practice, and its financial results highly profitable, especially as long as the Madonna ore held out. In all his successive enterprises, Eilers beautified the surroundings of his smelting plants and the one at Pueblo was no exception. The grounds around the offices and Mess House were beautifully landscaped and well kept. Any of the old time metallurgists who could trump up an excuse to stop at Pueblo en route never failed to do so and enjoy the hospitality of the Club House, with Eilers at the head of the table, and us younger members of the staff ranging down in order of seniority, the youngest member chaired with custody of the keys to the wine cellar and dispensing of the fine brands of Rhine wine the Company provided for entertaining its guests. Thus we youngsters had the privilege of personal acquaintance with many of the older men of the mining and metallurgical profession whose names are famous in the early history of mining in this country.

Eilers selected his staff with care and everyone of them knew that if he made good he was in line for the top. The plant became a real training school, and many of us owe whatever professional success we may have attained to the precepts and thorough basic training we received from Eilers, who came to be known as the “father of modern lead-silver smelting.”

Otto E. Hahn, a contemporary of Eilers, was the first Superintendent; junior to him came the brilliant Robert Sticht, who later was transferred to Montana to build and operate the Great Falls plant for Eilers, and who afterwards became famous by successfully working out the art of pyritic smelting of pepper ores at Mt. Lyell, Tasmania.

Immediately on my graduation in 1885, I entered Mr. Eilers’ service at Pueblo; as Assistant Assayer, later Chemist, and in 1889 I succeeded Hahn as Superintendent. Walter H. Aldridge followed me in the line of promotion up to Assistant Superintendent, when he me transferred to the Montana Plant; then followed H. Paul Bellinger, Frank M. Smith, and later Karl Eilers.

Karl had spent most of his vacations at the plant and thus shared in the training and experiences that meant so much to the rest of us. And after his return from studies in Germany, following his graduation from Columbia School of Mines in 1889, he came to Pueblo 1892 as a regular member of the staff and moved up through the successive grades. After he had served for a year as Assistant Superintendent. I felt he was fully qualified to take the place which I had held so long as personal assistant to his father. So, I took the initiative, and against the very generous protests from both father and son, and with secret reluctance, resigned my position as Superintendent in 1896 and move to other fields.

Karl continued with his father’s company until after it became merged with the other smelting companies into the American Smelting & Refining Co. Here he was given wider and wider fields of usefulness, especially in the construction and operation of the great Garfield copper smelter in Utah. From there he was called to New York, in 1903 and became in time a director and Vice President of the Company, serving until he resigned in 1920 to take up consulting practice.

In 1927 he was induced to accept the presidency of the Lenox Hill Hospital, a position he held until his death, the hospital prospering greatly under his wise direction. His interest in welfare work led him to take a leading part in the Associate Hospital Service of New York, of which he was the first president.

Karl joined the Institute in 1888. He served various times as Vice President and Director and was Treasurer from 1927 until his death. He was elected Honorary Member in 1933, a distinction universally approved, for his technical ability, his high character, and his unfailing devotion to the interests of the Institute.

Karl resembled his father in his sturdy, forthright character, his distinguished talents, thoroughness, broad sympathies, kindly nature, and a gift for friendship. He achieved a professional reputation worthy of his blood. His impressive figure, silver mane, and benign manner will be remembered by all who knew him.

I think I cannot end this sketch more fittingly than by passing on the identical words that Dr. Raymond used in his obituary of Karl’s father: “And this is my farewell, so far as earthly companionship is concerned, to my genial, upright, generous comrade through four and fifty years of loyal friendship and mutual trust unmarred by doubt or discord.”

Author Elsbeth Eilers (1864-1949) prepared the bulk of the material below. Some of the information came from Meta Caroline Adolphine Eilers around 1883.

Hans Eilers. B1691 Feb. 8. A porter at the Junkernhof, had his daughter baptized Anna Catherine at Ilsenburg (or found in the records of Ilsenburg). Son, JOHANN ACHATES EILERS?

JOHANN ACHATES EILERS. B1720 Nov. 5. Born in Ilsenburg. Married to Miss Elizabeth Roth (possibly found in the records at Druebreck).

1. JOHANN GEORGE EILERS. B1722 Feb. 23. At the time Achates was a servant at the Wernigerode Castle (possibly found in Druebreck).

2. Other Siblings?

On Feb. 12, 1730, an Achatz Eylers married Sophia Elizabeth Kannengeisser of Elbingerode. Achatz was a coachman at the Wernigerode Castle. Sophia was his second wife, suggesting Elizabeth Roth had died. By his second wife he had ‘many’ children (possibly found in the records of the Wernigerode Castle).

JOHANN GEORGE EILERS married? Johann George Eilers was employed as a stable boy of the Grand Duke by the Ducal stable master of Wernigerode. He later became a butler and lackey.

1. JOHANN FRIEDRICH EILERS. B1754 Feb. 2 – d 1827 Mar. 2.

2. Other Siblings.

JOHANN FRIEDRICH EILERS. B1777 Jan. 15th (oldest son of Johann George) married Sophie Charlotte Jaeger, daughter of convent gardener Johann Martin Wilhelem Jaeger (d1800 mar. 24) in Druebeck and Marie Eliz. (b1749 Sep 27 in Gardiol – d1833 May 26).

1. ERNST JULIUS ADOLPH FRIEDRICH EILERS. B1779 Dec. 22 – D1851 Jun. 7. Born in Wernigerode in the Hartz Mountains in the Kingdom of Hanover.

2. Daughter Johanne Christine Rosemonde Charlotte. B1782 Mar. 18 – D1853 Mar. 20th. She married the Burger and Castiron Fabricator Schmitt in Werniergode in Dec 12, 1833. She died in Suelzhayen.

3. Johann Christoph Wilhelm Friedrich. B1784 Dec. 17 – D1851 May 11 He was a gardener at Niederad near Frankfurt. He died in Mensfelden.

4. Daughter Marie Sophie. B1787 Oct. 31 – D1848 Apr. 28. She never married and died at Wernigerode.

5. Luise Henriette Joahnne Juliane. B1791 Feb. 14 – D1850 Jun. 7 Daughter. She married Christopher Mutter (or Meuller) in Ilfeld and died in Renkel.

ERNST JULIUS ADOLPH FRIEDRICH EILERS, nicknamed “Fritz.” He married Luise Elizabeth Roth, on Jan. 4th, 1805. Luise’s father was a pastor and her mother was born a Goeppel and died in Glasberg. Ernst’s wife Luise (born Feb 14, 1774) died at Sophienhof on Sep. 2, 1829. ERNST and Wife #1: LUISE ELIZABETH ROTH EILERS: married 1805 and had the following seven children:

1. Sophia. B1806 Jan. 16 – D1871 Oct. 28. Born at Gedern and died in Werni-gerode as the widow of Oberforester Kunkel.

2. Karl Ludwig Christian. B1807 Mar. 6 – D1876 Feb. 1. Born at Gedern was a minister and died at Suelzhayn. Married Jan. 31, 1837, Emma Henneritette Luise Wilhelminia Mueller, daughter of the Commission and teach of mathematics at Blankenberg. Her father was Carl Friedrich Wilhelem Mueller and mother was Johanne Sophie Hennriette Apfel, who was born at Blankenberg on Sep. 4, 1811, and died at Suelzhayn on Dec. 18, 1872. Anton Eilers’ daughter Else reports that Anton felt close to these kids.

a. Anna Augusta Ernestine. B1837 Nov. 29. Han Weber’s mother. Han married Anton’s daughter, Anna Eilers).

b. Meta Caroline Adolphine. B1839 May 11.

c. Erich Friedrich August. B1841 Mar. 16 – D1842.

d. Emma Caroline Franziska. B1843 Aug. 19 – died?

3. Ernst Ludwig Friedrich. B1809 Jan. 10 – died? born at Gedern. He was a Head forester at Sophienhof. He was married Nov 2, 1847 to Sophie Charlotte Hennriette Roth, daughter of district forester Friedrich Ludwig Roth and Johanne Friedrika Bartels Roth, born in Schierke on Dec. 7, 1821.

a. Friedrich Carl. B1848 Jul. 20 at Ilsenberg.

b. Charlotte Luise. B1850 Aug. 3 at Ilsenberg.

c. Luise Anna. B1854 May 31 at Christianenthal. Married a Forester named Teschner in Schierke.

d. Friedrich Ernest. B1855 Aug. 27 at Sophienhof.

e. Friedrich Louis. B1857 Dec. 10 at Sophienhof. (Karl E. Eilers knew as Friederich)

f. Frederike Charlotte. B1860 May 1 at Sophienhof.

4. Daughter Louise Frederike Anges. B1810 Oct. 29 – died? born at Sophien-hof. Married to Bergrath Brandes, who was a mining engineer. He was in charge of the Iron Works at Ilsenburg.

5. Frederike Caroline Wilhelmina.B1812 Jul. 4 – D1813 Nov. 15. Born in Gedern.

6. Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig. B1812 Jul. 4 – D1813 Nov. 15.

7. Carl Wilhelm Heinrich Eilers. B1816 May 18 – D1816 Oct. 6.

ERNST JULIUS ADOLPH FRIEDRICH EILERS, and Wife #2: ELIZABETH DIELMANN EILERS: married 1838 and had the following two children:

1. FRIEDRICH ANTON EILERS. B1839, Jan. 14 – D1917 April.

2. Emma Franziska Eilers. B1846, May 17 – D1874.

FRIEDRICH ANTON EILERS and Elizabeth Lizzie (Emrich) Eilers

1. Elsbeth (Else) Eilers. B1864 Feb. 10 – D1949 Jul. 17. (never married)

2. KARL EMRICH EILERS. B1865 Nov. 20 – D1941 Aug. 18.

3. Anna Eilers. B1867 Jun. 22 – d1944. (married step-cousin Hans Weber)

4. Luise Eilers. B1868 Nov. 5 – D1921 May 8. (never married)

5. Emma Eilers. B1870 Sep. 12 – D1951 Mar. 28. (never married)

6. Meta Eilers. B1875 Sep. 18 – D1921 May 23. (never married)

KARL EMRICH EILERS and Leonie Farny Wurlitzer

1. Marguerite Eilers. B1898 Jul. 31 – D1975 Apr. 23.

2. KARL FREDERICK “FRITZ” EILERS. B1899 Sep. 21 – D1971 Aug. 1.

3. Francis Farny Eilers. B1902 Apr. 4 – D1987 Jan. 26.

4. Hans Eilers. B1904 Nov. 6 – died soon after.