English Translation of Hahn’s 1938 Article on Karl Eilers

Below is the letter from Karl Eilers to Maxwell Hahn about an upcoming biography by Hahn on Eilers for a German newspaper. The German version can be found here.

March 15 1938 Letter from Karl to Mr. Hahn

Mr. Maxwell Hahn

Room 1811–570 Lexington Avenue .

New York City

My dear Mr. Hahn:

I was much pleased with your biographical article concerning myself, and I have done as you suggested– made a few corrections in pencil; also, I am having your article re-written, with some copies for my children.

On your last page you make a very nice and very proper comment about Frank Van Dyk. I wish you could also say something to the effect that I am very grateful for the friendly, congenial assistance given me and our Associated Hospital Service by Homer Wickenden and yourself; and if you do not think it would clutter up the article too much, I would also like to have recognized the fine assistance given us by Mr. Pyle, Wm. Breed, Jr., Mr. Stanley Resor, and the many other important members of our Executive Committee and the Board. I had thought that something could be said immediately after your paragraph about Frank Yan Dyk covering Homer and yourself. Perhaps to add the other names at this point might be too cumbersome; but if your ingenuity could work it in somewhere advantageously, I should like very much to have it.

Very truly yours,

enc.

KE/S;

=================

Maxwell Hahn’s biography draft of Karl Eilers (English Version):

“Because I wasn’t worried, and because I had confidence . . .”

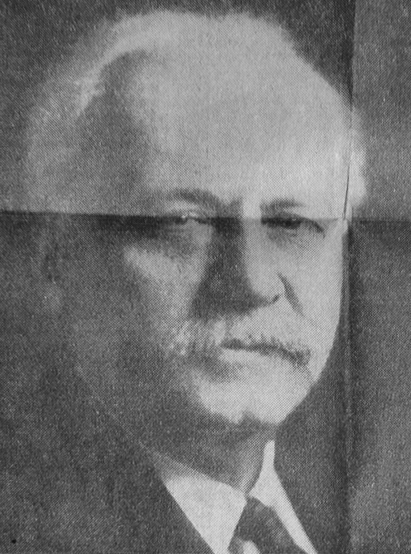

With these words, Karl Eilers, American-horn son of a German father, explains how he has traveled the long road from his birth seventy-two years ago in a small Ohio town to a position of prominence in New York City as President of the Associated Hospital Service of New York and President of Lenox Hill Hospital.

Today tall and portly, with the erect carriage of an army officer Karl Eilers is as full of confidence and faith in the future as in his youth. White-haired now, he goes about his tasks with the energy of a younger man and greets each day with the zest carried over from his colorful and adventurous past.

He has watched the Associated Hospital Service grow until now more than 650,000 men, women and children in the New York metropolitan area are enrolled and entitled to hospital care when needed. The skeptics who questioned the non-profit three-cents-a day plan for hospital care at its beginning less than three years ago have found their answer in the fact that subscribers have share and individually saved more than $3,7l5,000 in hospital bills.

And with the faith that enabled him to accept the presidency of the three-cents-a-day plan when others were doubtful of its success, Karl Eilers is convinced that enrollment in the plan will exceed in in York City a million members by the end of this year.

Mr. Eilers’ confidence in the idea of placing hospital care on the family budget for payments of a few cents each day has been strengthened by the confidence of the public.

But for a decision made eighty years ago, Karl Eilers might have been a ministers son, pursuing his destiny in Clausthal, in the Harz Mountains, Germany.

The decision was wade by his father, F. Anton Eilers, who, given the choice of the ministry or mining for a life’s work, decided to be a miner. He was sixteen at the time, and from America came reports of a great Western territory as yet hardly touched, and of minerals that slept under the grass roots, ready to yield their wealth to the finder.

And so, in 1859, Karl Eilers’ father came to America. He brought his small savings and a stout heart to a country soon to be torn with internal conflict. Slavery, not minerals, was the subject he heard discussed at every corner. In that year, a man named John Brown had led a raid on Harpers’ Ferry in Virginia to incite a slave revolt. John Brown was killed, but the issue grew sharper and sharper. There were rumors of war in the air. Disturbing rumors to the ear of the young man who had left a quiet home in Germany.

He found a Job in a clothing store on Chatham and Pearl Streets, and a place to live in the Tremont section of the city. He worked there for several years, meanwhile seeking an opportunity to carry out his determination to be a miner. In 1861 Civil War was declared. Mr. Eilers remained in New York. In 1863, when he was courting the girl who was to be Karl Eilers’ mother, the draft riots broke out in New York City and left 1,000 dead to decide whether or not Republican officials had stuffed the draft lists with the names of Democrats. But the violence of the times proved no handicap to romance and in that year Mr. Anton Eilers married.

Shortly after his marriage, he left the clothing store where he had been employed and started his career in the mining industry in an assay office on Park Row. His employer was Dr. Rossiter W. Raymond of Adelberg & Raymond, assayers.

Mr. Eilers and his young bride traveled about the country from one mining operation to another. In 1865, while with a company drilling for oil near Marietta, Ohio, his son, Karl Eilers, was born.

The first American-born son of the Eilers family opened his eyes in a perplexed country. Abraham Lincoln had been shot and torn from the helm of the nation when it most needed guidance. Andrew Johnson was inaugurated president of the United States and assumed leadership of a broken and uncertain people.

The family returned to New York and took up residence in the Morrisania section of the city. Young Karl Eilers developed into a tall husky boy, receiving his first formal education at a public school in the Melrose section. His father was advanced to the position of Deputy Mineral Surveyor. Dr. Raymond had become United States Com-

miasionor of Mining Statistics for the western part of the United States and had six men scouting around the country, gathering information concerning the mineral resources of the nation.

In 1873 Karl Eilers witnessed his first financial panic and saw a city demoralized. With business structures tottering the depression began with a series of bank failures on September 20. The Stock Exchange closed that day and remained closed until September 30. Dr. Raymond retired from his position in 1876. Karl Eilers’ father also resigned, and went to Colorado to investigate the copper resources there at the request of a Boston organization.

At Saints John, Colorado, Karl Eilers received the first indication that his life was one curiously favored by fate. He was in the flimsy shelter of a small smelting plant that had been set up at the foot of a towering mountain. He stood watching the progress of a rainstorm that had been raging about him for hours when he heard a roar as though the whole mountain were collapsing. Tree-roots, loosened by the torrents of rain, gave way. Tons of earth crumpled and roared down the mountainside, throwing a barrage or trees and rocks into space. It was useless to run. Karl Eilers watched the mountain as it flattened and spread towards him. When the slide had spent itself, the twisted trees and broken rocks were piled a scant fifty feet from the plant there Karl Eilers stood and breathed thankfulness.

Mr. Eilers left the exciting life he had led with his father in the west and returned to New York to study at the Hill School, Pottstown, Pa., and at the Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute in 1883. Later he took courses in mining and metallurgy at Columbia University.

In 1889 he finished his studies in America and returned to his father’s native Germany to study in Berlin. Interested in European mining operations, he visited France May, 1891 to see the mines there. While in Paris, he studied Spanish in preparation for a trip to Spain. He left for that country in fall and lived for several weeks at the American Embassy. Later he traveled through the southern part of that country, inspecting mining conditions.

Karl Eilers returned to the United States in 1892 and, like his father, arrived at a time when the country was in upheaval. Labor trouble had swept the land. Riots were frequent. He joined his father who had become a power in the mining industry and worked with him. In 1894, that industry, too, became the target of labor manipulations. A nation-side strike of miners paralyzed operations throughout the country. Again, the Eilers weathered the storm, moving alertly from one organization to another.

In 1896 at the age of thirty, Karl Eilers married. He had acquired a reputation by that time for his knowledge of smelting theory and practice, and in 1900 was sent to organize a lead smelting plant that the American Smelting and Refining company had built in Utah. The Guggenheins had taken control of the American Smelting and Refining Company in 1901, and his association with them lasted until 1920 when he parted company with Simon Guggenheim and his organization.

Recalling the problems met during his smelting career, Karl Eilers remembers that their troubles were not all under ground. The smoke that poured in great volume from the chimneys of the smelting plants made the smelters unpopular with the eastern farmers, and lawsuits were frequent. The farmers protested that their crops and animals were stifled by the rolling clouds and carried their complaints to the courts. Efforts were made to change this condition by building the plants at the mouths of canyons and valleys so that the smoke would be swept out and up by the air currents. These efforts were futile, however, and the smoke continued to sweep over the land for a radius of twenty-five miles and more from whore the plants were constructed.

But that, and the mountain slides, forest fires and ruggedness was part of the expansion and development of the West in which Karl Eilers played such an active part, It was to be, if cities were to grow where forests and empty plains stretched limitless and forbidding.

The men who met and solved the difficulties of that forced and hurried growth of a nation had to have confidence, they had to be unafraid.

In New York four years before Karl Eilers was born the second and more peaceful half of his destiny began shaping itself. The German Hospital and Dispensary was founded in 1861. Because of Civil War, the first building was not completed until 1868 although six beds were then in use at the dispensary which had been establish at 8 East Third Street.

It, too, expanded and developed. Now known as Lenox Hill Hospital, with modern buildings at 111 East Seventy-sixth Street it has taken its place as one of the leading hospitals in New York City.

When Karl Eilers was invited several years ago to become a member of the board of trustees of the hospital, he accepted because he ‘considered it a civic duty.’

Today, as president of Lenox Hill Hospital, he continues to regard his position as a fulfillment of a civic duty, one more contribution to a community he loves.

In 1934, he was asked to accept the presidency of the Associated Hospital Service of New York, a non-profit community organization that planned to put hospital care on the family budget of the man and woman in the metropolitan area for payments of a few cents a day.

There were critics of the idea, and others who warned Karl Eilers that it would not work.

“Why become associated with an organization that is pre-destined for failure”, they argued.

Enrollment rates had been estimated at $10 a year for a single subscriber. They were too low, the doubters pointed cut. Too many hospital benefits were provided, the cost of operation would be too great. And, anyway, the public would not be interested.

Karl Eilers shrugged his heavy shoulders. It was not a new idea to him. For in Pueblo, Colorado, many years ago, the miners and smelters had agreed upon a similar plan to ensure themselves proper care in times of illness and injury. From each man’s monthly rage was deducted a certain sum which was put into a central fund. From this fund, the money was taken when needed for medical care. The plan had worked well and served its purpose. And Karl Eilers had confidence in this plan to serve millions of people in the New York metropolitan area. He accepted the presidency.

Today, more and more people are learning that they don’t have to worry about unexpected hospital bills. Letters pour into the headquarters of the three-cents-a-day plan at 570 Lexington Avenue from grateful subscribers, stating that, because of their membership, they have been able to meet the problem of unexpected hospitalization without financial concern. The bills are paid in advance.

Every day, 1,198 incoming calls are handled by Associated Hospital Service telephone operators. Most of the calls are from persons who want to know more about the plan and its methods of enrollment. The doubters have been silenced, and Karl Eilers maintains his well-placed confidence in the plan and the people who are responsible for its success.

The three cents-a-day plan has upheld its standards as a non-profit community service. If it were otherwise, it is doubtful whether Karl Eilers would be associated with it.

He speaks proudly of Frank Van Dyk, executive director of the Associated Hospital Service of New York, and credits him with the growth of the plan and the extension of hospital benefits to subscribers.

[Large empty gap in the draft document at this location between the paragraph above and below. No obvious reason why]

He is proud, too, that as president he never interferes with the activities of his executives.

“One of the biggest things I have learned is to keep my hands off the man who is doing the work”, Karl Eilers explains. “I believe it was the father of John D. Rockefeller, who said, ‘Find the man that knows more about your problems than anyone else, put him in charge, and then let him work them out’”.

He looks up from his desk and smiles. Not a young man now, but certainly not an old man. With a past already filled with rich memories, he keeps his eyes to the future and the opportunities that may be in it for him to serve the community further.

Karl Eilers might have been a minister’s son, resigned to old age in Clausthal, in the Harz Mountains, Germany. He might have failed in the West and been swept aside by the waves of progress. He wasn’t.

“Because I wasn’t worried, and because I had confidence—“.